Contents

- Foreword

- Executive Summary

- Introduction

- Characteristics of Bassetlaw

- Overall Aims and Objectives

- Priority Actions and Timescales

- Work Programme

- Procedures

- General Liaison and Communication

- Liability and Enforcement

- Information Management

- Review Mechanisms

- References

- Appendix 1

- Appendix 2

- Appendix 3

- Appendix 4

- Appendix 5

- Appendix 6

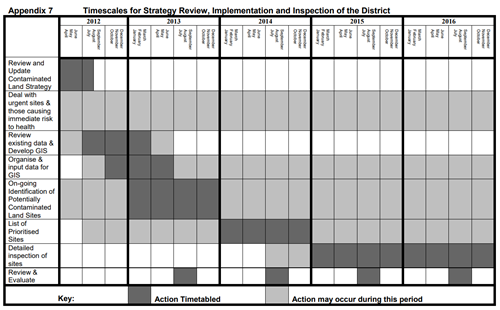

- Appendix 7

- Appendix 8

- Appendix 9

Foreword

"The quality of our land in Bassetlaw District is important to all of us, in terms of public health, ensuring continuing economic prosperity and enabling residents to enjoy our public spaces safely.

One of the council‟s overall objectives is to control threats to public health and the environment that could arise from contaminated land. This strategy sets out how we aim to achieve that.

We need to be able to identify where potentially hazardous sites might lie, assess the risks that they could pose to the community, and prioritise them so that the council can focus resources on where the risk is greatest.

This is a large task, but I am confident that the steps described in this strategy document will lead to better protection of our land, and of the people and the environment of Bassetlaw District."

Councillor Julie Leigh (Cabinet Member for Environment and Leisure)

Executive Summary

This strategy document details how Bassetlaw District Council will manage the duties it has in relation to contaminated land and potentially contaminated land sites within the district. These duties are contained within Part 2A of the Environmental Protection Act 1990.

Bassetlaw District Council first published a contaminated land strategy in July 2001, to detail how the council would take a rational, ordered and efficient approach to the inspection and investigation of land contamination. This revised strategy has been produced following a major revision to the statutory guidance in April 2012 and also takes into account other legislative changes since 2001.

The council has used all available information and a risk based approach during the initial screening process and will continue to do so when conducting any detailed inspection of sites to identify contaminated land. A rolling inspection programme will be undertaken, running until June 2015, with the council maintaining a public register of any land designated as contaminated.

The primary regulator in respect of these powers is the local authority, although it may be necessary to work with other organisations, particularly the Environment Agency in order to make a formal decision on contaminated land.

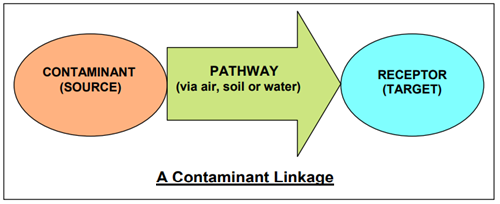

Under the definition contained within the legislation, in order for land to be designated as contaminated, a site must have both a pathway, by which significant harm may be caused (from the contaminant) and a specified receptor on which significant harm can be inflicted. If either the pathway or the receptor is missing from the contaminant linkage, the site may be in a contaminative state but cannot be designated as contaminated land. It is likely therefore, that only a very small proportion of sites will be designated as contaminated sites under the strict definition of contaminated land.

The identification of contaminated land will, therefore, be based firmly on the principles of risk assessment. Significant and imminent risks to human health will always be given the highest priority.

Potentially contaminated land will, prior to any detailed investigation, be prioritised and categorised according to a preliminary assessment of risk. This is to ensure that all further investigative work relates directly to the seriousness of the potential risk, so that the most pressing problems are identified and quantified first.

The council‟s approach in the main will be to seek voluntary remedial action (without the need for enforcement action) of any contaminated land where possible. An extensive consultation process will be completed and ample encouragement given to arrive at an informal solution.

The process of investigating and remediating land will ensure that all land in the district is suitable for use and does not pose unacceptable risks to people, the environment, water and property.

Introduction

Contaminated land is an issue which impinges upon all areas of Bassetlaw District Council's business and one which requires expertise from a variety of disciplines. It effects property transactions, marketing issues, planning, building control and even maintenance/works contracts all over the district. To be effective, the strategy must encompass all of these areas and provide a clear framework within which all departments must operate.

The statutory regime for the identification and remediation of contaminated land (under Part IIA of the Environmental Protection Act (EPA) 1990) has been implemented by Local Authorities since 2000. Under this regime, the Council is required to inspect land in its district for contamination. In July 2001 Bassetlaw District Council submitted a written strategy to the Environment Agency detailing how the authority will take a rational, ordered and efficient approach to this inspection. Following the publication of new statutory guidance produced by DEFRA in April 2012, a review and update of the strategy was required. The following document is Bassetlaw District Council‟s Contaminated Land Inspection Strategy, which details the authority‟s approach to dealing with its obligations under the contaminated land regime.

Background to the Legislation

The UK has a legacy of land contamination arising from past industrial development. Various industrial practices have led to substances being in, on or under land such as tars, heavy metals, organic compounds and mining materials. In addition, landfilling of waste sometimes took place without adequate precautions against the escape of landfill gases and leaching of materials. The previous regulatory system for dealing with contaminated land led in some instances to over prescriptive remediation being demanded to ensure public safety and as a result emphasised the need for a new system of regulation.

The Government, in its response to the 11th report of the Royal Commission on Environmental Pollution in 1985, announced that the Department of the Environment was preparing a circular on the planning aspects of contaminated land. The draft of the circular stated that:

"Even before a planning application is made, informal discussions between an applicant and the local planning authority are very helpful. The possibility that the land might be contaminated may thus be brought to the attention of the applicant at this stage, and the implications explained."

In 1988 the Town & Country Planning (General Development) Order required local planning authorities to consult with waste disposal authorities if development was proposed within 250 metres of land that had been used to deposit refuse within the last 30 years. Thus suggesting that it would be advantageous for the planning authorities to have available a list of potentially contaminated sites.

In January 1990 the House of Commons Environment Committee published its first report on contaminated land. This document, for the first time, expressed concern that the Government‟s suitable for use approach, “... may be underestimating a genuine environmental problem and misdirecting effort and resources”. The committee produced 29 recommendations, including the proposals that:

"The Department of the Environment concern itself with all land which has been so contaminated as to be a potential hazard to health or the environment regardless of the use to which it is to be put, and;

“The Government bring forward legislation to lay on local authorities a duty to seek out and compile registers of contaminated land."

Immediately following the House of Commons report the Environmental Protection Act 1990 had at section 143, a requirement for local authorities to compile, „Public registers of land which may be contaminated‟. If enacted this would have required local authorities to maintain registers of land, which was, or may have been contaminated, as a result of previous (specified) uses. In March 1992 however, the concern about the blighting effect of such registers resulted in a press release published by the Secretary of State delaying the introduction of section 143 stating:

"The Government were concerned about suggestions that land values would be unfairly blighted because of the perception of the registers."

Subsequently, in July 1992, draft regulations were released with significantly reduced categories of, contaminative uses, “.... to those where there is a very high probability that all land subject to those uses is contaminated unless it has been appropriately treated”. It was estimated that land covered by the registers would be only 10 to 15% of the area previously envisaged. This, however, still did not satisfy the city, so on the 24th of March 1993 the new Secretary of State (Michael Howard) announced that the proposals for contaminated land registers were to be withdrawn and a belt and braces review of land pollution responsibilities to be undertaken.

This resulted in the Department of the Environment consultation paper, Paying For our Past (March 1994), which elicited no less than 349 responses. The outcome of this was the policy document, Framework for Contaminated Land, published in November 1994. This useful review emphasised a number of key points:

- The Government was committed to the 'polluter pays principle' and, 'suitable for use approach'

- Concern related to past pollution only (there were effective regimes in place to control future sources of land pollution)

- Action should only be taken where the contamination posed actual or potential risks to health or the environment and there are affordable ways of doing so, and

- The long standing statutory nuisance powers had provided an essentially sound basis for dealing with contaminated land

It was also made clear that the Government wished to:

- Encourage a market in contaminated land;

- Encourage its development, and

- That multi functionality was neither sensible nor feasible.

The proposed new legislation was first published in June 1995 in the form of section 57 of the Environment Act which amended the Environmental Protection Act 1990 by introducing a new Part IIA. After lengthy consultation on statutory guidance this came into force on 1st April 2000.

The Contaminated Land (England) Regulations 2006 were introduced to elaborate on various details of the Part 2A regime, such as dealing with issues of what qualifies as a “special site”; public registers; remediation notices; and the rules for how appeals can be made against decisions taken under the Part 2A regime.

In April 2012 DEFRA published new statutory guidance which intended to explain how local authorities should implement the regime, including how they should go about deciding whether land is contaminated land in the legal sense of the term. This revised statutory guidance while still taking a precautionary approach allows regulators to make quicker decisions about whether land is contaminated under Part IIA preventing costly remediation operations being undertaken unnecessarily. It also offers better protection against potential health impacts by concentrating on the sites where action is actually needed.

Explanation of Terms

The legislation and guidance is very heavily punctuated with many complex and often unusual terms. To assist in the interpretation of these an extensive glossary has been included in DETR Circular 2/2000, Environmental Protection Act 1990: Part IIA Contaminated Land. (For convenience this has been reproduced in Appendix 1 of this strategy document).

National Objectives of the Regime

The Government believes contaminated land to be “an archetypal example of our failure in the past to move towards sustainable development”. The new regime is based upon a set of principles that include „suitable for use‟ standards of remediation, the „polluter pays‟ principle for allocating liability and a "risk based‟ approach to the assessment of contamination.

The first priority on land contamination has therefore been specified as the prevention of new contamination via proposed and existing pollution control regimes.

Secondly there are three stated objectives underlying the "suitable for use‟ approach to the remediation of contaminated land, as follows:

- To identify and remove unacceptable risks to human health and the environment;

- To seek to bring damaged land back into beneficial use; and

- To seek to ensure that the cost burdens faced by individuals, companies and society as a whole are proportionate, manageable and economically sustainable.

The suitable for use approach recognises that risk can only be satisfactorily assessed in the context of a specific use with the aim of maintaining an acceptable level of risk at minimum cost, thereby, “not disturbing social, economic and environmental priorities”.

The specific stated objectives of the regime are:

- To improve the focus and transparency of the controls, ensuring authorities take a strategic approach to problems of land contamination;

- To enable all problems resulting from contamination to be handled as part of the same process (previously separate regulatory action was needed to protect human health and to protect the water environment);

- To increase the consistency of approach taken by different authorities; and

- To provide a more tailored regulatory mechanism, including liability rules, better able to reflect the complexity and range of circumstances found on individual sites.

In addition to providing a more secure basis for direct regulatory action, the Government considers that the clarity and consistency of the regime, in comparison with its predecessors, is also likely to encourage voluntary remediation. It is intended that companies responsible for contamination should assess the likely requirements of regulators and plan remediation in advance of regulatory action.

There will also be significant incentive to undertake voluntary remediation in that the right to exemption to pay Landfill Tax will be removed once enforcement action has commenced.

The regime has also assisted developers of contaminated land by reducing uncertainties about so called, “residual liabilities”, in particular it should:

- Reinforce the suitable use approach, enabling developers to design and implement appropriate and cost-effective remediation schemes as part of their redevelopment projects;

- Clarify the circumstances in which future regulatory intervention might be necessary (for example, if the initial remediation scheme proved not to be effective in the long term); and

- Set out the framework for statutory liabilities to pay for any further remediation should that be necessary.

Local Objectives

Bassetlaw District Council is implementing Part IIA of the Environmental Protection Act 1990, which compliments the Council‟s own corporate aims and objectives.

Bassetlaw is committed to its key Mission Statement, which is:

"We aim to secure the best quality of life for everyone in Bassetlaw"

and a vision to deliver:

"A dynamic district where people live, work and prosper and the council works in partnership with others to develop a better quality of life for all".

Bassetlaw is also focused on four ambitions, which this strategy contributes towards, these are:

- Economic Regeneration of our District

- Quality Housing and Local Environment

- Involved Communities and Locality Working

- A Well-Run Council

In 2010 Bassetlaw District Council adopted its Sustainable Community Strategy for the period 2010 - 2020. This strategic plan establishes Bassetlaw District Council‟s determination to improve and promote the following eight priority policy areas:

- Enterprising Communities

- Learning Communities

- Sustainable Communities

- Healthier Communities

- Stronger Communities

- Safer Communities

- Supporting Children and Young People

- Accessible Communities

These key areas are not independent of one another – there is a great deal of interrelationship between them. They also reflect central government policy and the priorities of Nottinghamshire as a whole, outlined in the Nottinghamshire Sustainable Community Strategy 2010-2020.

This Inspection Strategy is presented in the context of Bassetlaw‟s Strategic Plan. Six of the priority policy areas are particularly relevant to this strategy document, as follows:

Enterprising Communities - Regenerate Key Areas of Bassetlaw

By encouraging brownfield re-development through voluntary remediation and providing specialist advice to potential developers, contaminated land can be safely recycled to the benefit of the local community.

Sustainable Communities - Conserve and Expand Areas of Open Green Space

The identification and safe re-use of contaminated land is an important part in the sustainable development of Bassetlaw‟s area. The contaminated land inspection strategy will make an increasingly significant contribution to sustainable development within Bassetlaw.

Supporting Children and Young People - Ensure the Safety of Children and Young People and Reduce the Risks to Children and Young People.

Much land contamination has been present for long periods of time. Limited controls were placed on land which poses significant risks. The strategy will ensure that the risks from such land is identified and reduced or removed.

Similarly, Bassetlaw's Core Strategy sets out 10 strategic objectives, four of which this Inspection Strategy will assist in the achievement of. These are:

- SO3 To prioritise the community regeneration opportunities available in Harworth, Bircotes, Misterton and Carlton-in-Lindrick / Langold by developing brownfield sites in these settlements in advance of greenfield allocations.

- S05 To ensure the continued viability of Bassetlaw's rural settlements through the protection and enhancement in the levels, of local services and facilities and support for enterprises requiring a rural location.

- S08 To protect Bassetlaw's natural environment by maintaining, conserving and enhancing its characteristic landscapes, biodiversity, habitats and species and seeking quantitative and qualitative growth in the green infrastructure network across and beyond the District.

- S09 To protect and enhance Bassetlaw's heritage assets, identify those of local significance, advance characterisation and understanding of heritage asset significance, reduce the number of heritage assets at risk and ensure that development is managed in a way that sustains or enhances the significance of heritage assets and their setting.

Several other key corporate, regional and county strategies influence this contaminated land inspection strategy.

The East Midlands Regional Plan provides a broad development strategy for the region.

The plan seeks to realise the following vision for the Northern Sub-Area, in which Bassetlaw is located:

- The Northern Sub-Area will be an area containing vibrant towns and smaller centres which are easily accessible from major transport routes, which is rich in carefully protected natural and cultural assets and supporting a viable population and employment base within sustainable communities.

- Of particular relevance to Bassetlaw are: policies 7 (Regeneration of the Northern Sub-Area); 13a (Regional Housing Provision); 19 (Regional Priorities for Regeneration);

- and Northern SRS policies 1 (Sub-Regional Development Priorities); 2 (Supporting the Roles of Towns and Village Centres); and 3 (Sub-Regional Employment Regeneration Priorities). While there are no targets for employment land provision set out in the RSS, these policies do seek to ensure the delivery of 350 houses a year within Bassetlaw (7000 houses in total between 2006- 2026).

While the Core Strategy and Development Management Policies document will set out a local vision for the area, and specific policies to achieve that vision, we must also ensure that the document conforms to national planning policy. National planning policy is set out in the National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF), which can be found via the website http://www.communities.gov.uk. A key message within this document is delivering Sustainable Development, which makes it clear that sustainable development is the core principle underpinning planning. In simple terms, this means ensuring that development meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.

These various strategies as well as providing support to Bassetlaw‟s Strategic Plan show that the identification and safe re-use of contaminated land plays a key part in the sustainable development of Bassetlaw and its surrounding area.

Regulatory Context of Contaminated Land

The Act itself states at section 78B (1) that:

Every local authority shall cause its area to be inspected from time to time for the purpose -

- Of identifying contaminated land; and

- Of enabling the authority to decide whether any such land is land that is required to be a special site (see Appendix 2).

Section 78B (2) states that the authorities must act in accordance with guidance issued by the Secretary of State in this respect. Statutory Guidance has been published within the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs, Environmental Protection Act 1990: Part 2A, Contaminated Land Statutory Guidance document.

The statutory guidance makes clear that in order to carry out this duty authorities must produce a formal contaminated land strategy document which clearly sets out how land which merits detailed individual inspection will be identified in an ordered, rational and efficient manner, and in what time scale.

The strategy was first completed, formally adopted by Bassetlaw District Council, and published in July 2001. The strategy has now been reviewed and updated. Copies of the final document must also be forwarded to the Environment Agency. Subsequently the strategy must be kept under periodic review.

In order to satisfy the far reaching objectives of the regime it will be necessary to investigate land throughout the whole of the district and collate significant volumes of information. This will ultimately enable Bassetlaw District Council to make the sometimes difficult and inevitably complex decisions relating to its condition, the risks it presents and who may be liable for it by law. This strategy is the foundation of that process and seeks to express as clearly as possible how each stage will be addressed.

Regulatory Role of Bassetlaw District Council

The primary regulator in respect of these powers is the local authority. In Bassetlaw District Council, the strategy will be under the control of the Director of Community Services. It should be noted that this is a complex and demanding enforcement role that will be carried out in accordance with the responsibilities laid upon the Authority by this particular piece of legislation and the Cabinet Office Enforcement Concordat of 1998.

The statutory guidance states:

“Inspection duty and the decision whether land is contaminated land remains the sole responsibility of the authority”

This is a significant responsibility that reflects existing local authority duties under the statutory nuisance regime and Town & Country Planning, development control. The role in broad terms includes:

- To prepare a strategy for the inspection of contaminated land in the area

- To cause the area to be inspected to identify potentially contaminated sites

- To determine whether any particular site is contaminated (by definition)

- To determine whether any such land should be designated a „special site‟ (see Appendix 2)

- To act as enforcing authority for contaminated land not designated as a „special site‟

Where the presence of contaminated land has been confirmed, the enforcing authority must:

- Prepare a written record of any determination that particular land is contaminated land

- Establish who should bear responsibility for remediation (appropriate person(s))

- Decide after consultation what must be done in the form of remediation and ensure it is effectively carried out

- Determine liability for the costs of the remedial works

- Maintain a public register of regulatory action in relation to contaminated land

Regulatory Role of the Environment Agency

The Environment Agency has four main roles in regulating contaminated land:

- To assist local authorities in identifying contaminated land (particularly where water pollution is involved)

- To provide information and advice to local authorities, including site specific guidance on contaminated land where requested

- To act as enforcing authority for contaminated land designated a „special site‟

- To publish periodic reports on contaminated land nationally

A special site has a statutory definition (see Appendix 2). In general, special sites have had uses where the Environment Agency is likely to already have a regulatory responsibility, for example sites regulated under the Integrated Pollution Control regime. . Special sites are not necessarily more contaminated than other kinds of site. Examples are nuclear sites, MOD sites, oil refineries and sites that may cause pollution of drinking water resources.

A memorandum of understanding has been drawn up between the Environment Agency and the Local Government Association (on behalf of all local authorities) that lays down the roles and responsibilities of both parties under Part IIA of the Environmental Protection Act 1990: Contaminated Land.

Definition of Contaminated Land Under Part 2A

Whether land is considered as contaminated will depend on the definition used. Section 78A(2) of Part IIA defines Contaminated land as:

“Any land which appears to the local authority in whose area it is situated to be in such a condition, by reason of substances in on or under the land, that -

Significant harm is being caused or there is a significant possibility of such harm being caused; or

Significant pollution of controlled waters is being caused, or there is a significant possibility of such pollution being caused”

The definition aims to enable the identification and remediation of land on which contamination is causing unacceptable risks to human health or the wider environment. Subsequently, the definition does not include all land where contamination may be present.

Within this document, all references to contaminated land take their meaning from this statutory definition.

What may and may not constitute the various categories of harm is described in the statutory guidance (see Appendix 3).

Controlled waters include inland freshwater, groundwater and coastal waters (for further information see Appendix 4).

Principles of Risk Assessment & Contaminant Linkages

The definition of contaminated land is based on the principles of risk assessment. The statutory guidance defines „risk‟ as the combination of:

- The likelihood that harm, or pollution of water, will occur as a result of contaminants in, on or under the land; and

- The scale and seriousness of such harm or pollution if it did occur

The Council must search its districts for land that has both sensitive receptors (i.e. something that may be harmed, see below) and sources of potential contamination. Where the Council has good reason to believe these both exist, it must undertake a formal risk assessment in accordance with established scientific principles in order to establish whether there is the potential for them coming together and causing harm or pollution as described. This is known as a contaminant linkage. If there is no contaminant linkage, the substance cannot cause harm.

A “contaminant” is a substance which is in, on or under the land and which has the potential to cause significant harm to a relevant receptor, or to cause significant pollution of controlled waters.

A “receptor” is something that could be adversely affected by a contaminant, for example:

- a person,

- an organism,

- an ecosystem,

- property,

- controlled waters.

A “pathway” is a route by which a receptor is or might be affected by a contaminant.

All three elements of a contaminant linkage must exist in relation to particular land before the land can be considered potentially to be contaminated land under Part 2A, including evidence of the actual presence of contaminants. The term “significant contaminant linkage”, as used in the Guidance, means a contaminant linkage which gives rise to a level of risk sufficient to justify a piece of land being determined as contaminated land. The term “significant contaminant” means the contaminant which forms part of a significant contaminant linkage.

It is important to fully understand this concept, as it will form the basis of all future site investigation and prioritisation procedures.

Where the Council is satisfied that significant harm is occurring, or there is a significant possibility of such harm to land or controlled waters, it must declare that a significant contaminant linkage exists and that the land is therefore contaminated land by definition. In every case where the land does not fall within the category of a special site, the local authority must commence regulatory action.

The statutory guidance promotes a risk-based approach to dealing with potentially contaminated land in the UK. The aim of this type of approach is to protect human health and the environment without unnecessarily wasting finances on cleaning up sites that do not pose a significant risk.

This „suitable for use‟ approach acknowledges that the risk presented by a level of contamination will largely be dependent upon the use of the land, in addition to factors such as the geology of the site. Therefore, a site may be remediated to a level acceptable for use as a car park but not for residential use. Subsequently, risks need to be assessed on a site-by-site basis of the facts.

Land can only be considered contaminated if it impacts in a certain way on specified receptors. The receptors defined in the statutory guidance recognised as being potentially sensitive are:

- Human beings

- Ecological systems:

- Areas of Special Scientific Interest (Wildlife & Countryside Act 1981, section 28)

- National / Local Nature Reserves (Wildlife & Countryside Act 1981, section 35 /National Parks & Access to the Countryside Act 1949, Section 21)

- Marine Nature Reserves (Wildlife & Countryside Act 1981, section 3)

- European Sites (Conservation of Habitats and Species Regulations 2010 regulation 8)

- any habitat or site afforded policy protection under paragraph 6 of Planning Policy Statement (PPS 9) on nature conservation (i.e. candidate Special Areas of Conservation, potential Special Protection Areas and listed RAMSAR sites)

- Property:

- Buildings (including below ground)

- Ancient Monuments

- Property:

- All cops including timber

- Produce grown domestically or on allotments for consumption

- Livestock

- Other owned or domesticated animals

- Wild game subject to shooting or fishing rights

- Water:

- Territorial seawater (to three miles)

- Coastal waters

- Inland fresh waters (rivers, streams, lakes, including the bottom / bed if dry)

Ground Waters (Water Resources Act 1991 s104)

In summary, for contaminated land to exist the following are prerequisites:

- One or more contaminant substances

- One or more specified receptors

- At least one plausible pathway between contaminant and receptor (then a contaminant linkage exists)

- A good chance that the contaminant linkage will result in significant harm to one of the specified receptors

The Conceptual Site Model

The process of risk assessment involves understanding the risks presented by land, and the associated uncertainties. In practice, this understanding is usually developed and communicated in the form of a “conceptual site model” (CSM) which indicates all the contaminant linkages and uncertainties associated with each.

Strategic Approach to Identification of Contaminated Land

The Council is required to take a strategic approach to inspecting land in its area for contamination.

The statutory guidance requires that the approach adopted should:

- Be rational, ordered and efficient

- Be proportionate to the seriousness of any actual or potential risk

- Seek to ensure the most pressing and serious problems are located first

- Ensure resources are concentrated on investigation areas where the authority is most likely to identify contaminated land

- Ensure that the local authority efficiently identifies requirements for the detailed inspection of particular areas of land

In developing a strategic approach to the identification of contaminated land Bassetlaw District Council will need to have regard to its own local circumstances and in particular consider:

- The extent to which any specified receptors (as defined in list above) are likely to be found in the district

- The history, scale and nature of industrial or other potentially contaminative uses

- The extent to which any of the specified receptors is likely to be exposed to a contaminant

- The extent to which information on land contamination is already available

- The extent to which remedial action has already been taken by Bassetlaw District Council or others to deal with land contamination problems

In undertaking its duties to inspect the district under section 78B (1) of the Act, the Council will take into consideration the particular characteristics of the area, including:

- Relevant geology, hydro geology and hydrology

- The location of:

- sensitive water receptors

- sensitive property receptors

- relevant ecological receptors

- all existing human receptors and;

- Potential sources of contamination

Situations Where This Regime Does Not Apply

The primary aim of the Government is to prevent new contamination occurring. There are several situations therefore where existing pollution control legislation would apply to control the effects of land contamination:

- The Environmental Damage (Prevention and Remediation) Regulations 2009 are a result of the implementation of the European Directive on Environmental Liability (2004/35).

They are based on the principle of „the polluter pays‟, where those responsible for a pollution incident are required to prevent and, where necessary, remedy any environmental damage caused. The emphasis is on the „operator‟ identifying where or when there is imminent threat or actual damage to the environment, and taking immediate action.

Environmental damage is considered to be:

- Serious damage to surface or ground water.

- Serious damage to EU-protected natural habitats or species.

- Contamination of land with a significant risk of harm to human health.

The regulations are not retrospective and will only be applied to damage caused after their implementation.

-

Pollution Prevention and Control (Environmental Protection Act 1990 Part I/ Prescribed Processes and Environmental Permitting (England and Wales) Regulations 2010) - This regime has been introduced to replace IPC, and includes the specific requirement that permits for industrial plants and installations must include conditions to prevent the pollution of soil; and there are also requirements in relation to the land filling of waste.

-

Waste Management Licensing (Environmental Protection Act 1990 Part II) - All waste disposal and processing sites (including scrapyards) should be subject to licensing. Contamination causing harm, or pollution of controlled waters, should be dealt with as a breach of the conditions of the licence. In exceptional circumstances, where the problem arises from an unlicensed activity, it is possible that Part IIA could apply. An example of this would be a leak from an oil tank outside the tipping area. Where there has been an illegal tipping of controlled waste (fly tipping) this should also be dealt with under the Environmental Protection Act 1990, Part II (section 59).

-

Discharge Consents (Water Resources Act 1991 Part III) - No remediation notice can require action to be taken that would affect a discharge authorised by consent.

-

Risk of Harm to Employees - Where there is a risk of harm to persons at work from land contamination, this should be dealt with under the Health and Safety at Work etc Act 1974. The enforcing authority will be either the Health & Safety Executive or this Council depending on the work activity.

- Change of Land Use - Where land becomes a risk to potential new receptors as a result of a change of use, the Town & Country Planning Development Control regime will continue to apply as before. The National Planning Policy Framework (2012) states that: Planning policies and decisions should ensure that:

- the site is suitable for its new use taking account of ground conditions and land instability, including from natural hazards or former activities such as mining, pollution arising from previous uses and any proposals for mitigation including land remediation or impacts on the natural environment arising from that remediation;

- after remediation, as a minimum, land should not be capable of being determined as contaminated land under Part IIA of the Environmental Protection Act 1990; and

- adequate site investigation information, prepared by a competent person, is presented.

The Building Regulations (made under the Building Act 1984) requires measures to be taken to protect new buildings, and their future occupants, from the effects of contamination. “Approved Document Part C (Site Preparation and Resistance to Moisture)” published in 2004 gives guidance on these requirements.

In addition there are several other situations where the relationship with Part IIA may need clarification:

- Contaminated Food (Food Standards Act 1999) - Part I of the Food and Environment Protection Act 1985 gave Ministers emergency powers to prevent the growing of food on, inter alia, contaminated land. Following the establishment of the Food Standards Agency this power is now vested in the Secretary of State. Where the Council suspects crops may be affected from contaminated land to such an extent they may be unfit to eat, they will consult the Food Standards Agency and Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (DEFRA) to establish whether an emergency order may be necessary. It should be noted, however, that remediation of the site if necessary would be carried out through the powers in Part IIA.

- Radioactivity - The Part IIA Contaminated Land Regime was extended to cover radioactivity in 2006 in England and Wales. The Council will liaise with the Environment Agency where radioactive contamination is suspected or confirmed.

- Organisms - Part IIA does not apply to contamination caused by organisms such as bacteria, viruses or protozoa, as they do not fall within the definition of substances. This could affect land contaminated with Anthrax spores, Ecoli, etc. The Council will liaise with the Environment Agency in relation to MOD land and DEFRA on all other sites. It should be noted that even though contaminated sites used in connection with biological weapons must be designated Special Sites (see Appendix 1); this applies only to non-biological contamination.

- Statutory Nuisance - (Environmental Protection Act 1990 Part III) - The relationship between Part IIA and statutory nuisance is not straight forward. If land is declared contaminated land by definition, it cannot be considered a statutory nuisance. This is understandable and ensures there is no duplication or confusion between the two regimes. If however, the land is investigated and found not to be contaminated land but, “land in a contaminated state” (defined as land where there are substances in, on or under the land which are causing harm, or there is a possibility of harm being caused), it also cannot be considered a statutory nuisance for the purposes of Part III of the Act. Precisely in what circumstances might land be declared, “in a contaminated state”, is not clear. Where land is not contaminated land or in a contaminated state, but is causing a nuisance from smell, it could be considered a statutory nuisance as before.

Inspection Strategy Development

The identification of contaminated land will be carried out in an ordered, rational and efficient manner based firmly on the principles of risk assessment. Significant and imminent risks to human health will always be given the highest priority.

Any strategy on contaminated land can only be as good as the information upon which it is based. Due to Bassetlaw‟s proactive approach to contaminated land, the Environmental Health Service has collated large amounts of information on sites that have the potential to cause contamination due to a former land use. In line with the statutory guidance, the inspection strategy will therefore be focused on areas where contaminated land is thought likely to exist and on industries specific to the area.

In order to meet these requirements, the framework for the original inspection strategy was partially developed through the Nottinghamshire Contaminated Land Sub-Group. The group consists of Environmental Health representatives from each of the eight Local Authorities that form Nottinghamshire. There are also representatives from Leicester City Council and The Environment Agency (EA). The sub-group reports to the Nottinghamshire Pollution Working Group (NPWG) that in turn reports to the Nottinghamshire Chief Environmental Health Officers Group. The NPWG has been in existence since the late 1980‟s. It was established to provide technical and practical information on pollution matters for the Chief Officers Group. It enables a collaboration of expertise across the County to provide a coherent approach to environmental issues.

The Sub-Group was formed to concentrate solely on contaminated land to enable officers to share information and expertise to provide a consistent and efficient approach to the implementation of Part IIA of the Environmental Protection Act 1990. In pursuance of this, it was decided that certain sections of the strategy were drafted collectively. Each local authority drafted a section of the strategy document, using “Contaminated Land Inspection Strategies – Technical Advice for Local Authorities” issued by the Department of the Environment, Transport and the Regions for reference. The aim of this exercise was to provide each local authority with a detailed framework on which to base its own strategy in order to promote a consistent approach across the county. Each section was discussed and amended where appropriate to produce a structured and consistent strategy based on the collective expertise of the eight local authorities.

Internal Team Responsibilities

Within Bassetlaw District Council, the Environment and Health Services has responsibility for the implementation of the Contaminated Land Regime. When the regime was first implemented in 2001 an Environmental Health Officer was seconded to undertake the work necessary to produce the initial Contaminated Land Inspection Strategy. During the development of the strategy it became apparent that the most appropriate way of meeting the statutory obligations of the new contaminated land regime would be to have a designated officer tasked with delivering the inspection strategy and co-ordinating the various links that other council services will have to the regime. A pollution control officer is now in post who has the responsibility of reviewing and implementing the strategy.

The Pollution Control Officer (Contaminated Land) will report directly to the Principal Environmental Health Manager (Food, Health and Safety), who in turn reports to the director of community services. This Pollution Control Officer will be responsible for the implementation of the strategy once approved by elected members and for coordinating any detailed site investigations that are required, overseeing any subsequent remediation work, ensuring data is managed correctly, consultation on planning applications and providing information on general enquiries. District Environmental Health and Technical Officers and Officers from other council services will support the Pollution Control Officer, where necessary. It is likely that private consultants, yet to be determined, may be required to carry out any detailed inspections of sites in order to assist in the determination of contaminated land, unless the necessary expertise can be found from within the Council. Any work of this nature will be co-ordinated by the Pollution Control Officer.

The Pollution Control Officer (Contaminated Land) can be contacted at:-

Environmental Health

Bassetlaw District Council

Queen's Building

Potter Street

Worksop

Nottinghamshire

S80 2AH

Tel: 01909 534423

This strategy impacts on potentially all departments of the Council and therefore to necessitate its smooth implementation formal working links with the following services have been formed:

Planning and Development Control

The inspection of the district will identify areas of potentially contaminated land which may already be developed, awaiting development, derelict, protected or green belt. This may result in the need to re-examine past development control files or identify development routes for contaminated sites that may subsequently impact on the Local Development Plan.

Building Control

Have the duty to enforce protection measures in new build projects to mitigate the impact of contamination on property. Information they hold will be essential to quantify risks.

Legal Services

This is a highly complex piece of legislation that could have significant implications for the Council, landowners and occupiers. The Solicitor‟s advice may be required on many aspects including those relating to enforcement, liability, powers of entry, data protection, access to information etc.

Information Technology

Significant volumes of data will need to be held both on database and geographical information systems. Support will be required on the use of these systems and data protection.

Finance

This legislation can have significant resource implications for the Council, both as an Enforcing Authority and landowner.

Environmental Health (Neighbourhoods Team)

May hold information on pollution incidents, reports and complaints relating to specific sites, which will need to be reviewed and able to provide assistance in enquiries and determination of contaminated land. Likely to be the first contact point for any complaints relating to issues of contaminated land.

Council Owned Land

Land owned by or in use and controlled by Estates, Housing, Leisure Services, Engineers, and Environment Services may be contaminated and require remediation. In addition planning may need to be consulted for issues relating to remediation and tree growth and impacts on eco-receptors.

Highways - responsibility of Nottinghamshire County Council

Land under highways, pavements, verges and common areas may be contaminated and present a risk to potential receptors. The regime may therefore impact on Nottinghamshire County Council as the Highways Authority must maintain registers under Part III of the New Roads and Street Works Act 1991 regarding streets with „‟special engineering difficulties”. This includes risks from contamination.

Progression of Inspection Strategy Through the Council

The progression of the Contaminated Land Inspection Strategy through the Council to its adoption and final publication has been as follows:

- Forward draft strategy for comments to external Statutory Consultees

- Submission of draft strategy for comments to Cabinet for comment and recommendations for consultation with the local community

- Submit amended strategy to Management Team for approval

- Forward amended strategy to executive Committee for approval, adoption and recommendation for formal publication

- Publish and publicise final version of the adopted strategy and submit to the Environment Agency

Characteristics of Bassetlaw

Characteristics of Bassetlaw District Council

This section gives background information about the area covered by Bassetlaw District Council. It also gives an indication of the local issues that need to be considered in order to identify the likely existence of a contaminant linkage and ultimately to make a determination on statutory contaminated land.

An overview of Bassetlaw District Council

Geographical Location

Bassetlaw District Council was established in 1974 and is responsible for local government in the areas formerly administered by Worksop Borough, Worksop Rural District, Retford Borough and Retford Rural District Councils. It is the most northerly District Council in Nottinghamshire, situated between agricultural Lincolnshire and industrial South Yorkshire. Bassetlaw‟s boundaries approximate 155km in total and coincide with major landscape features such as the River Trent on the east, which also forms the county boundary with Lincolnshire and the forests and parks of the Dukeries on the south. To the north and west, the district extends to the boundary with South Yorkshire. The A1/A1M runs the length of Bassetlaw District, between Worksop and Retford.

Bassetlaw‟s local authority neighbours are Bolsover and Mansfield to the south west, Newark and Sherwood to the south, West Lindsey to the east and Doncaster and Rotherham to the north and west respectively.

Size

Overall the district is 63,687 hectares. Bassetlaw occupies almost 30% of the County‟s area but has only 10% of the population.

Population Distribution

The 2010 population estimate records 111,315 residents within Bassetlaw, comprising 27 constituency wards and 70 parishes. The main economic and population centres are Worksop (population 41,450) and Retford (population 21,941). Populations in the remaining parishes are as follows: -

Table 1: Population figures based on the 2010 population estimates Office of National Statistics

| Parish | Population |

|---|---|

| Askham | 200 |

| Babworth | 1420 |

| Barnby Moor | 260 |

| Beckingham | 1215 |

| Bevercotes | 25 |

| Blyth | 1267 |

| Bole | 115 |

| Bothamsall | 195 |

| Carburton | 65 |

| Carlton-in-Lindrick | 5969 |

| Clarborough | 1140 |

| Clayworth | 285 |

| Clumber and Hardwick | 85 |

| Cottam | 95 |

| Cuckney | 285 |

| Dunham on Trent | 310 |

| East Drayton | 220 |

| East Markham | 1150 |

| East Retford | 21,941 |

| Eaton | 220 |

| Elkesley | 690 |

| Everton | 785 |

| Fledborough | 60 |

| Gamston | 305 |

| Gringley on the Hill | 675 |

| Grove | 110 |

| Harworth and Bircotes | 7693 |

| Haughton | 35 |

| Hayton | 415 |

| Headon-cum-Upton | 180 |

| Hodsock | 2550 |

| Holbeck | 310 |

| Laneham | 280 |

| Lound | 515 |

Bassetlaw’s Historical Development and Industrial Legacy

Worksop Area

As far as early records show, industries began in Worksop during the Middle Ages and were connected to products from the land such as malting, milling and timber. These basic industries, with certain modifications, have survived through to modern times. During the 17th and 18th centuries, Worksop was noted for its liquorice and a thriving trade developed. This industry gradually died out following more lucrative finds of liquorice in Pontefract.

Worksop benefited from the opening of the Chesterfield Canal in 1777, which gave a boost to local industries, allowing Worksop to expand. It also brought about a reduction in the price of coal due to reduced transport costs.

The early part of the 19th century saw the arrival of the railways with a corresponding great demand for timber (that was abundant in the area) and the first colliery was sunk at Shireoaks. This began a new era of industrial activity and growth in Worksop. By the end of the 19th century quarrying had commenced at Steetley both for magnesian and limestone. Shortly after the turn of the 20th century following the sinking of a shaft at Manton (1902) and the opening of a flour mill (Smiths) on Eastgate, a profound change took place in the town owing to the ease of access to these sites and the beginnings of the modern town took shape.

Maltkilns were present in Worksop as long ago as 1636 and probably for many years before that. The malting business being widely carried on due to much of the land being extensively devoted to the growth of barley. In medieval times, when Worksop Priory geographically formed the centre of a number of religious houses, Worksop was well noted for the quality of its malt. By the middle of the 19th century malting was the principal trade, with Worksop paying more duty than any other place in England. Various breweries owned a number of the maltkilns. Clinton Maltkilns (close to the railway station on Carlton Road, Worksop) was owned by a well-known maltster of Mirfield and Wakefield. The same maltster owned maltings at Gateford Road, Kiveton Park, Tuxford and Retford. By 1860s, 29 maltkilns were present in Worksop:-

- 5 near to the canal between Golden Ball and Bridge Place

- 6 were on or near Gateford Road

- 4 dispersed between Potter Street and Eastgate

- 3 were on Lowtown Street

- 2 on Abbey Street

- 1 each on Clarence Road, Carlton Road, Park Street and Castle Street

The malting business continued to flourish until the end of the 19th century. By the early 1900s an increase in the larger factory like maltkilns caused the smaller ones to go out of business and many of the buildings were subsequently demolished.

Flour milling was another occupation as old as the town of Worksop itself. It is likely that the first settlers ground grain by hand worked stones, but their successors harnessed the power of the River Ryton. In 1636 there were 3 water mills for flour milling, but by the end of the 19th century only 2 mills were still in business, Beard‟s Mill (a water mill fed by the River Ryton) and a steam mill at Gateford Road.

For centuries trees were felled in woodlands surrounding Worksop. Even until the early 18th century timber was the main house building material. Following the availability of brick, less timber was used, but it wasn‟t until the development of the Chesterfield Canal and the opening out of the railways that the local wood yards became an important source of employment. In 1897, there were 8 large timber firms in the town, some specialising as timber merchants, others as turners or chairmakers. By 1930s the last of the Worksop chairmaking had stopped.

Sand quarrying grew up in the Worksop area as a result of the geological structure of the locality. The Bunter Sandstone in the area is a deep stratum with a shallow overburden, which allowed three grades of sand to be quarried: medium or red sand, inferior and fine sand. Gateford Quarry produced sand for the steel industry whilst Sandy Lane Quarry provided for the building trade as well as the steel industry. Fine Sand was quarried from the site east of Owday Lane and a further sand quarry was Located at Kilton Hill.

Magnesian limestone has been quarried in the district due to the geological structure of the locality. A magnesian limestone belt that touches the western boundary of the Worksop area provided limestone for use in the Sheffield steel industry. Quarrying stone at Steetley goes back to the 12th century. Records for the quarry existed until 1880, with Steetley providing stone for the many ducal houses of the area, for York Minster and the Houses of Parliament. The growth of Steetley quarry resulted from the discovery that magnesian limestone could be converted into a refractory material suitable for furnace lining. In the late 1800s 2 refractories were started, one sited alongside Steetley Quarry the other in Sandy Lane and began producing bricks and tiles.

Coal mining has been an important industry for Worksop and consequently has helped to shape the settlements and landscape as we know it today. The sinking of the first shaft at Shireoaks colliery in 1859 brought coal mining to the town and before the end of the century collieries were also working at Steetley and Whitwell. In 1897 the first of the two shafts was sunk at the future Manton Colliery, which by 1907 was completely operational.

With the outbreak of the Second World War there was an increase in the commencement of heavy industry in the Worksop area. During the 1950s lighter manufacturing industries such as hosiery were introduced.

Retford Area

Retford has always been a market town receiving its Royal Charter in 1246. In 1766 the Great North Road was re-routed through Retford, further increasing the importance of the area around the market square and making it a highly desirable area to work and live.

Milling was Retford‟s earliest recorded industry, with the town building several windmills to take advantage of its position of being in the centre of a large corn growing area. The presence of so many mills created the need for machinery, which led to the setting up of several engineering works in the area. Surprisingly, sailmaking was another important early industry in and around Retford. Boats on the Trent used sails at a time when West Stockwith was a busy port. Narrow boats on the Chesterfield Canal were also equipped with sails for river work. Also, sailcloth was used on the early windmills before the wooden slatted sweeps were invented. The sailcloth was made from the flax that was widely grown in Nottinghamshire in the early 19th Century.

Retford's thriving market status created the demand for a variety of goods and trades such as:-

- Hatmakers

- Boot and shoemakers

- Saddlers

- Malsters

- Brewers

- Tinners

Retford's prosperity was afforded by the fact that it could supply most needs and services itself.

By the 1960s industries such as mining, forestry and agriculture accounted for 25% of the total employment in the whole area, with mining being regarded in Worksop as the basic industry.

Current Land Use Characteristics

The majority of Bassetlaw is rural in nature with a large number of attractive villages and towns and pleasant countryside. Bassetlaw‟s rural area accommodates around half of the population within 68 parish communities. The development of the District has been greatly influenced by the past reliance on coal mining. There are now no operational mines in Bassetlaw District; the last two were at Welbeck and Harworth, although Harworth could still re-open. The villages of Shireoaks, Rhodesia, Carlton, Langold and Harworth/Bircotes largely grew up to accommodate colliery workers. Both Retford and Worksop are also manufacturing centres. Traditional industries (textiles, metal goods, engineering, agriculture etc.) continue as significant sources of employment, but considerable progress has been made throughout the District in diversification into new sectors of employment in order to improve the economy and reduce the level of unemployment.

The town centres of Worksop and Retford contain the greatest concentrations of retail, commercial and business activities in Bassetlaw. Worksop‟s origins lie in heavy industry and coal mining, but both of these activities have declined, and the town is now mostly residential with some light industry. To the south of Worksop lies Clumber Park, part of Sherwood Forest. This area is mostly rural with large wooded areas.

Retford was originally a market town. It is now, like Worksop primarily residential, and contains some light industry although less than Worksop. The area east of Retford is flat, open country, mostly farmland, dotted with small villages. Along the eastern border at the side of the River Trent are two coal fired power stations, located at: West Burton and Cottam.

Residential Land Use

The total number of properties located throughout Bassetlaw is approximately 49,800, split mainly between the population centres of Worksop and Retford. Approximately 14% of the dwellings are council owned (6,938 at March 2011). In addition there are a number of privately owned permanent residential caravan sites (mobile home sites).

Industrial and Commercial Land Use

In general terms the Bassetlaw district can be divided into the more industrialised west and the agricultural east with its numerous villages, the A1 separating the two.

Local industries that have a fairly long association with Bassetlaw and that are still in operation include: coal mining, quarrying, glassware production, refractory products, printing works, rubber works, textile manufacture, engineering and waste processing.

Two of the former colliery sites (Manton and Shireoaks) have been cleared of buildings and the spoil heaps have been re-graded and have been planted with grass and trees for proposed leisure activities. In order to sustain and improve the economy of the area Bassetlaw was invited to prepare an Enterprise Zone scheme for land at Manton Wood, Worksop. Designated as such in 1995, Manton Wood has already attracted companies concentrating on distribution and food and drink manufacture.

Between 1994 and 2011, the Nottinghamshire draft Mineral Local Plan has allocated 683 hectares of Bassetlaw land for approximately 15 million tonnes of aggregate extraction.

Any site with the potential to cause contamination will be identified at the investigation stage of the work programme (detailed in Part 5).

A list of some of the current potentially contaminative uses already identified within the District is described below:

- Bassetlaw has 20 Part A processes authorised by the Environment Agency under the provisions of the Pollution Prevention and Control Act 1999 for integrated pollution prevention and control (IPPC) including two power stations, 15 waste sites and crude oil storage and handling premises. The IPPC regime should control unauthorised discharges to land, but their presence will need to be noted and the potential for long term pollution assessed, particularly post closure.

- Currently, there are 2 Part A2 processes and 41 Part B processes under the Pollution Prevention and Control Act 1999 regulated by the District Council including one pet food manufacturer, one mushroom composting process, one animal rendering process, eight cement batching plants, one rubber works and two timber treatment processes. To date, 12 petrol stations are permitted under the same legislation. There have been no leakage problems from these premises in the last two years.

- In addition to these there are a number of premises throughout the district that have or have had licensed petroleum stores on site. Bassetlaw District Council will work with the Petroleum Officer (based within the trading Standards Department at Nottinghamshire County Council) to identify these premises and assess the likely risks.

- Extractive Industries: Between 1994 and 2011, the Nottinghamshire draft Mineral Local Plan has allocated 683 hectares of Bassetlaw land for approximately 15 million tonnes of aggregate extraction.

- This Council is a Hazardous Substances Authority for the purposes of the Planning (Hazardous Substances) Act 1990 and the Planning (Hazardous Substances) Regulations 1992. This legislation requires consent to allow the presence on land of hazardous substances above a specified quantity. These regulations were recently amended by the Planning (Control of Major Accident Hazards) Regulations 1999 to take account of the new COMAH Regulations. There are currently 6 authorised sites in the District. The Environmental Health Unit maintains a register for this purpose.

- COMAH sites - The Control of Major Accident Hazards Regulations 1999 are enforced by the Environment Agency and Health & Safety Executive (joint competent authority) to control both on and off site risks from industries with a high potential for disaster from dangerous substances (flammable, toxic or explosive). There are 2 sites within the District that are currently designated as tier 1 COMAH sites.

Community Land Use

A significant proportion of land within Bassetlaw is used for institutional purposes such as hospitals and schools and recreational or open space areas. The district council itself owns and maintains a substantial amount of recreational and open space (outlined in section 2.3 below).

In addition, Nottinghamshire County Council owns or has owned significant land and property holdings within the Bassetlaw boundary. The portfolio of County Council owned land currently comprises:

- 56 primary schools

- 14 schools / training college sites

- 11 factory sites

- 19 social services / community buildings

- 9 public library sites

- 3 administration offices

- 7 staff / caretakers houses

- 3 refuse disposal sites

- 1 vacant and highway land sites

- 1 public weighbridge

- 2 grit hopper sites

- 11.86 hectares of land (including highway land)

Other non-council uses of land within Bassetlaw include:

- HM Prison, Ranby

- Bassetlaw NHS Trust Hospital, Worksop (main site) and Retford (administration centre)

- Gamston Airport

- Ministry of Defence Land

- Recreational e.g. National Trust, National Forest

Transport Infrastructure

Bassetlaw is well located in relation to communications. The A1 (south to Newark)/A614 (south to Nottingham) form the backbone of the District, which is bisected east-west by the A57 Sheffield-Lincoln route.

The railways have played an important part in Bassetlaw‟s industrial past. The opening out of the railways in the middle of the 19th century allowed for direct access with the manufacturing districts of Lancashire, Sheffield and Manchester. Today, The GNER East Coast Main Line runs North-South through Retford and the Regional Railways Sheffield to Lincoln line through Worksop. The Robin Hood Line links Worksop with Nottingham. Land owned by railways is often left in a derelict state because it has no particular use or it is difficult to access. These areas are often used to accumulate unwanted materials and for illegal dumping.

Agriculture

Agriculture remains the predominant land use of Bassetlaw‟s area accounting for 78% of the District‟s land. Of the estimated 49,700 hectares, the proportion of different agricultural activities is as follows:

- 75% Arable (37,275 hectares)

- 10% Poultry and pig farming (4,970 hectares)

- 10% Cattle (2,982)

- 4% Sheep (1,988 hectares)

- 5% Dairy (2,485)

*Accurate as of 2001 (This type of data is no longer collected in this way)

Sewage Disposal

Bassetlaw District Council owns and maintains a number of small sewage treatment works (rotating biological compacters) that serve council housing at Carburton and Gamston.

Severn Trent Water has 26 small treatment works located throughout the district that it is responsible for. These works are all located near to surface water courses to accept the cleaned effluent. Discharge consents for the clean effluent are set and monitored by the Environment Agency.

Waste Disposal

Waste disposal by landfilling has occurred within Bassetlaw. 43 landfill sites have previously been identified within the district, by:

- Examining internal records from planning and building control sections

- Examining historic records and maps

- Using information from the County waste regulation office, and

- Collating local knowledge on sites.

Twenty two of these sites were in operation prior to licensing in 1974. One has been identified as an illegally operated site that was used for scrap vehicles and refuse, which closed in 1975. At fourteen of the identified sites there is either little or no information on the type of material dumped or the date the site closed.

Land Owned By Bassetlaw District Council

The Council and its predecessors (pre-1974) own or have owned (or have had an interest) in significant land and property holdings within the district boundary. There are a wide variety of external recreational facilities and public open spaces in Bassetlaw, many of which are provided directly by the Council. Bassetlaw owns 468 hectares of land used for this purpose. Langold Lake and Sandhill Park are two of the largest recreational areas in the district, which are in the control of the Council.

The portfolio of land and property holdings owned or leased by Bassetlaw currently comprises:

- 6,938 council houses

- 8 industrial estates

- 4 admin & operational buildings

- 2 civic buildings

- 1 museum

- 1 tourist information centre

- 20 community centres and sheltered housing schemes

- 18 car parks

- 2 marketplaces

- 12 miscellaneous property

- 16 other buildings

- 29 land holdings

- 2 sports centres

- 2 other arts and leisure facilities

- 1 golf course

- 48 parks and open spaces sites

- 7 public conveniences

- 3 cemeteries

- 916 rented garages and garage sites

- 31 leased shops

- 1 war memorial

- 14 allotment sites

Geology of the Area

Bedrock Geology

Knowledge of the geology is essential for understanding both the history and nature of the area. The underlying bedrock determines the physical shape and appearance of the land, which in turn may provide a pathway for contaminants to migrate e.g. gases along faults and fissures. Geological deposits can also influence the development of local industry in the area e.g. coal reserves, gravel and sand in the district. The geology also affects the presence and movement of groundwater and surface water. The bedrock geology itself can also act as a source of contamination e.g. naturally occurring radon gas.

The rocks that underlie Bassetlaw are mainly sedimentary rocks of the Jurassic, Permo-Triassic and Carboniferous age that were laid down between 150 – 350 million years ago. Superficial deposits overlie the bedrock in many areas. These are the deposits that have been laid down in the last 2 million years and the present day.

The following table illustrates the order in which the deposits were laid down within the district.

|

Geological Deposits underlying the Bassetlaw Area |

||

|---|---|---|

| Pleistocene Period and Present Day (2 million years ago up to present day) | Superficial deposits | Brown sand Alluvium Tufa Gravel Glacial sand Boulder clay |

| Jurassic Period (150 million years ago) | Bedrock deposits | Shales Limestone |

| Permo-Triassic Period (200 million years ago) | Bedrock deposits | Bunter Sandstone Keuper Marls |

| Upper Carboniferous Period (300 million years ago) | Bedrock deposits | Upper coal measures (sandstones) Middle coal measures Lower coal measures Millstone Grit |

| Lower Carboniferous Period (350 million years ago) | Bedrock deposits | Carboniferous Limestone Series |

The geology to the west of the Bassetlaw area comprises small areas of coal measures overlain by the Cadeby Formation. This narrow band along the western edge of the area is separated from the overlying strata by the Edlington Formation. East of Worksop, the Edlington Formation is overlain directly by Sherwood Sandstones (Bunter). This is intervened north west of the district (Oldcotes, Langold) by Brotherton Formation. The outcrop of the Sherwood Sandstones underlies the majority of the area and continues out towards the east of the district where it is overlain by the Mercia Mudstones, forming a low escarpment. All the strata dip gently to the east at an angle of 2-3 0. Some properties on the north western edge of the district may be affected by naturally occurring radon gas from the underlying limestone.

The coal measures that underlie the district have been extensively worked since the mid 19th century by means of a number of deep mines (some still worked today). As a result of mining there is a higher risk of mine gas migration and many of the voids left behind have been infilled with colliery spoils and other wastes, thereby exacerbating the problem of ground gas.

In a number of instances aggregate extraction (sand and gravel) has led to the exposure of geologically important sites.

Superficial Geology

This is the material that has been deposited on the bedrock geology over the last 2 million years. Recent superficial deposits, including sands, gravels, silts and clays commonly overlie these strata throughout the area. They can be glacial in origin, but alluvial deposits associated with river systems are a more dominant feature. Within the district significant alluvium and terrace deposits are present as a consequence of the Rivers, Trent, Idle, Ryton and Maun.

Further information on the occurrence of the bedrock and superficial geology of the Bassetlaw District can be found in the following geological maps, supplied by British Geological Survey:-

- Doncaster Sheet 88

- East Retford Sheet 101

- Chesterfield Sheet 112

- Ollerton 113

Information for the following section has been taken from: Environment Agency Guidance: Local Environment Agency Plan (LEAP) Idle and Torne Action Plan October 2000; Lower Trent and Erewash Local Environment Agency Plan (LEAP) Environmental Overview April 1999. National Rivers Authority: 1994 Policy and Practice for the Protection of Groundwater; Groundwater Vulnerability of Nottinghamshire. Sheet 18

Hydrogeology of the Area

Hydrogeology is the relationship between geology and groundwater. Geological strata capable of containing exploitable quantities of groundwater are termed aquifers. Abstractions from these aquifers provide water for potable water supplies and varied industrial and agricultural uses. Some aquifers are highly productive and are of regional importance as sources for public water supply while lower yielding aquifers may also be important on a more local basis. Groundwater provides a proportion of the base flow for many rivers and watercourses. In England and Wales groundwater as a whole constitutes approximately 35% of water used for public supply. Groundwater is usually of high quality and often requires little treatment prior to use. However, it is vulnerable to contamination from both diffuse and point source contaminants, from direct discharges into groundwater and indirect discharges into or onto land (NRA, 1994).

Principle Aquifers These are layers of rock or drift deposits that have high intergranular and/or fracture permeability - meaning they usually provide a high level of water storage. They may support water supply and/or river base flow on a strategic scale. In most cases, principal aquifers are aquifers previously designated as major aquifer.

Secondary Aquifers These include a wide range of rock layers or drift deposits with an equally wide range of water permeability and storage. Secondary aquifers are subdivided into two types:

Secondary A - Permeable layers capable of supporting water supplies at a local rather than strategic scale, and in some cases forming an important source of base flow to rivers. These are generally aquifers formerly classified as minor aquifers;

Secondary B - Predominantly lower permeability layers which may store and yield limited amounts of groundwater due to localised features such as fissures, thin permeable horizons and weathering. These are generally the water-bearing parts of the former non-aquifers.

Secondary Undifferentiated - Has been assigned in cases where it has not been possible to attribute either category A or B to a rock type. In most cases, this means that the layer in question has previously been designated as both minor and non-aquifer in different locations due to the variable characteristics of the rock type.

Unproductive Strata - These are rock layers or drift deposits with low permeability that have negligible significance for water supply or river base flow.

Within Bassetlaw, Principle Aquifers comprise of the Sherwood Sandstone Group and the Cadeby and Brotherton Formations. The Sherwood Sandstone aquifer underlies the majority of the Bassetlaw area and is used for the public drinking water supply by Severn Trent Water and Anglian Water Services. Groundwater in the Sherwood Sandstone aquifer flows in an east to north-easterly direction. The aquifer is heavily utilised and the patterns of abstraction cause some stretches of river to contribute water to the aquifer while others receive water from it. Over-abstraction has caused falling water levels and environmental damage in some areas.

This Sherwood Sandstone stratum continues right across the east of the district and under the Mercia Mudstone. The significance of this is that abstractions that take place out of Bassetlaw‟s boundaries will have a knock on effect on the water resources in the Sherwood Sandstone area.

To the west of the Sherwood Sandstone aquifer is the Cadeby Formation aquifer, which is less permeable and results in poorer yields of groundwater.

Principle Aquifers in the area, comprise sandstones in the Edlington Formation and Coal Measures. They also comprise the following superficial deposits: blown sand, alluvium, river terrace deposits, glaciofluvial sand and gravel deposits and sandy till. Principle aquifers may occur beneath secondary aquifers.

The area at the boundary of the principle aquifer (Sherwood Sandstones) and unproductive area (Mercia Mudstones) and along the River Trent boundary is classified as a secondary aquifer with overlying soils of both high and intermediate leaching potential.